Malaria in Pregnancy: Social and Behavior Change Communication Strategy Guidance Available

The SBCC for Malaria in Pregnancy: Strategy Development Guidance was developed to help SBCC and malaria in pregnancy (MiP) program managers and stakeholders address identified gaps and improve SBCC strategies and interventions for MiP, especially those interventions that target healthcare workers.

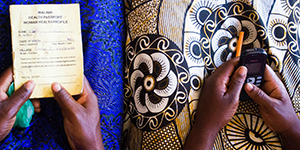

A young woman, pregnant for the first time and worried about whether or not to seek care for fever faces a number of obstacles, particularly if she lives in Sub-Saharan Africa. Even if she does have the means to seek care, she relies completely on her health care provider for essential medicines. Many pregnant women who sought care for fever, and those who could not, are not receiving the medicine they need. As a result, pregnant women deliver prematurely, with severe anemia, or lose their child due to malaria infection.

Pregnant women in areas with stable malaria transmission are often unknowingly infected with malaria. Malaria parasites sequester themselves in the human placenta and go undetected by rapid blood-based tests. For this and other reasons, malaria infections during pregnancy are not always diagnosed or treated, leading to serious negative health outcomes for mothers and their unborn children. The proven method of preventing this risk all-together is to give pregnant women preventive medicine (referred to as intermittent preventive treatment of malaria in pregnancy, or IPTp). When taken monthly after quickening, IPTp will prevent malaria infection. Fortunately this drug is cheap, safe, and incredibly effective. Recent studies have even found it prevents some sexually transmitted infections in addition to preventing malaria. One modeling study has estimated that an additional 215,000 low birth weight deliveries could be prevented each year if IPTp were administered to all women attending at least three antenatal care visits in malaria endemic regions of sub-Saharan Africa. Some countries advertise the name of this drug and encourage women to ask for it at their regularly scheduled antenatal visits. Other countries simply encourage antenatal attendance and expect clinicians to provide the drug according to protocol. Unfortunately a growing body of evidence shows low use of this life-saving drug.

Initial research on low uptake of preventive medicine for pregnant women focused on pregnant women, inquiring why they were not attending antenatal care visits or not demanding IPTp. More and more articles, including studies with larger and larger sample sizes, multi-country reports and systematic reviews, are finding that pregnant women in sub-Saharan Africa are attending antenatal care as instructed. Few reports find that pregnant women know of or can name a drug that prevents malaria in pregnancy. Most often where antenatal care attendance is high, IPTp uptake is suboptimal or low, leading researchers to ask if provision of IPTp might be a key constraint. Indeed, as more and more reports come in, it appears service providers often fail to procure adequate stores of IPTp, often fail to provide it to clients regularly, and in some instances mistreat their clients such that pregnant women do not return for their remaining scheduled appointments. Service delivery improvement programs exist, but do not yet appear to be adequately increasing provision of this essential drug. National malaria control programs in sub-Saharan Africa partner with a number or organizations that work to improve maternal health. Many organizations work to improve service delivery, others work to create demand for services at the community level. Increasingly, it appears better coordination between the two is necessary.

The Provider Behavior Change I-Kit provides step-by-step guidance on using SBCC to change provider behavior, and thereby improve client outcomes.

The Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) has synthesized existing program reports and peer-reviewed literature to determine what community and service provider factors facilitate or deter IPTp uptake. Results from findings have informed the development of guidance on how to better design social and behavior change communication (SBCC) strategies to prevent malaria in pregnancy. This guidance focuses on developing national strategies that address drivers of behavior for both service providers and communities. The focus of this guidance is new: service providers have not traditionally been seen as potential recipients of SBCC. Work HC3 has been doing to address service provider behavior change across a number of health areas (HIV/AIDS and family planning) has helped articulate malaria-specific concerns.

Many of the issues to consider in this guidance are country-specific. Rather than give users a number of globally applicable silver bullets (which clearly do not exist), this guidance draws attention to time-honored SBCC processes with a new focus on service providers. While the reasons for low IPTp uptake are known and finite, the understanding of how to find out which apply to a specific country are not being followed. Country strategies are often generic, failing to seek or provide any detail about local perceptions, attitudes, beliefs, or motivations. Audiences are poorly segmented, integration between malaria and maternal and child health units is often unclear, and communication and behavior objectives are commonly confused. This new strategy guidance walks users through a standard process of inquiry, prioritization of behaviors, and strategic, evidence-based decision-making about how to most effectively influence behaviors that prevent malaria in pregnancy. The hope is that service delivery and SBCC practitioners alike will improve their approach to preventing malaria in pregnancy, and that more work will be done in collaboration.

Malaria in pregnancy has long been seen as a completely preventable source of needless mortality and death. Until recently, pregnant women have been the recipients of any number of programs, initiatives and incentive schemes attempting to drive up provision and use of IPTp. With the processes, evidence, and proof that past efforts have been imperfect, it is time leaders changed tack and started working together to improve provision and demand for this life saving commodity. Please visit our SBCC for Malaria in Pregnancy: Strategy Guidance site and share it with others.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!